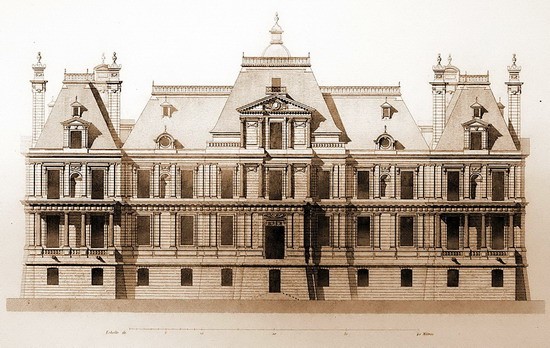

Chateau de Maisons-Laffitte

Summary

The Chateau de Maisons-Laffitte is Versailles before Versailles. The palace built by François Mansart opens its doors to the young Louis XIV at a sumptuous party held in April 1651. The Sun King will later call on sculptors and decorators from the Château de Maisons, as well as the architect’s nephew, for the Versailles works, Jules Hardouin Mansart.

The Chateau de Maisons-Laffitte was designed by François Mansart (1598-1666), one of the best architects in France, and built between 1640 and 1649. It was built for René De Longueil, a great man of the new French bourgeoisie (he became a minister, Surintendant des Finances of France, for a short time, in 1650).

It was about replacing an old mansion in Maisons sur Seine, the head of the family manor, a little more than 15 km from the center of Paris, next to the Seine river, where it could be reached. Laffite is the surname of the famous banker who bought it in 1818 and sold much of his land, which was invaded by numerous “villas”. The place, next to the forest (Fôret) of Saint Germain, was ideal to host the King (Louis XIII: 1601-1643), on his way to his hunting residences.

Chateau de Maisons-Laffitte Project

It is the most complete and best preserved building by François Mansart. It has always been considered a masterpiece. Jacques François Blondel, in his famous Cours d’Architecture of 1771, asserts that “every year we travel to Maisons with our students to convince ourselves that Mansart is the god of Architecture”.

In this work, Mansart used himself thoroughly, until the conclusion of it, and it is a completely his work until it is his beautiful gates. He had an unlimited budget, and acted without limitations: the expense was said to have amounted to 12 million pounds. Mansart adjusted everything to his own criteria, as he liked, because his imagination continually invited him to improve.

Anecdote

The pamphlets called Mansarades, spread an anecdote that was the following: “That was Mansart. As soon as a part of the Chateau de Maisons was built, he had it torn down without notifying the owner. Of course, this instability is inexcusable in someone as skillful as he in his profession” (Daziller, Fameux, 349, Mansarade 3). It is not proven; but it reflects the reality that the architect did whatever he wanted.

This work at its completion shows good sense and refinement. If you compare this mansion with the Chateau d’Ancy le Franc, you can see how much has been learned in the treatment of volumes and surfaces. But Maisons also differs from contemporary projects, such as Lemercier’s, for its perfect harmony, and at the same time for its imagination: the numerous variants that he is capable of introducing.

The building has a certain pomposity without being pretentious and a graceful elegance without frivolity. The effect is due to small tics, which impart a certain nervous vigor, and relieve the sensation of absolute balance and formality. They are the characteristic contribution of Mansart.

Ground plan

The house is of medium size compared to other noble chateaux, as befits a well-positioned bourgeois on the social scale. He is older than he often appears to the non-French observer. Confusing the size of the French windows that are very large compared to the doors

The house rises as if it were an exhibition object at the bottom of a platform, surrounded by a moat. At that time, having a moat was a matter of nobility, since it had no defensive function.

Walls or fences that would hinder the views were also avoided.

The front avenue would be framed by the constructions intended for trades and stables, destroyed in the 19th century; ahead were the very pretty guardhouses at the entrance.

In the front of the house, in the background, some very short arms advance, the minimum to insinuate a courtyard, and the small lateral bodies of its ends have small but marked concave exedras on their flanks.

The general volume is made up of the central forebody that advances a little, and the lateral pavilions: their masses stand out thanks to the combination of roofs (perfect silhouette: neither very busy nor uniform).

Top cornice

On the top cornice, short pediments, a few skylights on the axis of each area (not the openings) and some slender chimneys preserve something of the picturesqueness of previous times; but above all they mark very well the three axes, with their hierarchy: main and lateral (note the difference between the two facades).

In the back, the gardens were developed until they reached the river. Several representations are known. Among them, a Marot project.

Facade

They are executed entirely in stone, which gives them a particular nobility. Instead of the strong polychromy imposed by the usual combination of brick and stone, the composition of the facades is based on the relief -small changes in level- and a much more careful ornamental punctuation.

As in the previous buildings, the elevations are clearly defined by horizontal lines, which here are complete and well-proportioned entablatures. The roofs are also clearly drawn (nice, the start of the central roof), and the ridge line is underlined.

The surfaces fully and smoothly articulate with the pilasters which are usually double. The entablatures are proportionate, and form an anodyne grid with intercolumns of also reasonable proportion, which has been conceived to inscribe the window.

The central streets are superimposed on the avantcorps (reminiscent of the Chateau d’Anet), with more force in the lower body, leaving a small balcony; they are combined with the pediments and lateral porticoes. Extending over the entire surface and using properly proportioned elements, the grid is a classical “system” or frame of orders, and much more rigid than in the compositions of earlier times; and you would think you were a bit naive: almost a recipe.

Mansart’s ingenuity is found in the facades. It is not possible to describe these facades in detail: they must be examined. The recipe composition is full of its little tricks, which give a juicy variety. The entrance facade is more serious, with its pediments.

The garden façade

The garden façade takes advantage of the height of the moat, with greater showiness (it looks over the adjacent gardens); and thanks to the introduction of decorative niches, a resource already proven in previous works, it achieves greater variety. The niches break the uniform rhythm of double pilasters, which is only used in the corners; they are located in the centers of each area, and take over the axes of the composition, reinforced by the skylights. On the sides the small porticos appear, with a strange smaller intercolum in the center (and with larger intercolumns in front of the openings).

When you look at the building, you would think it impossible to design this residence any other way. It is perfect in its genre; and then it is understood that he has taken many hours of design and demanded a perfect execution in stone. It would be time to look at other works that, in comparison, are conventional, hackneyed, unskillful, and often clumsy.

Distribution

As the residence is not very large, it is resolved in a single extended bay; With this, in addition to achieving a notable development of the façade with just under 70 m, the rooms enjoy light and views from both sides.

The building is made up of two equivalent floors, which probably originally distinguish the summer apartments (below: more humid and shady), and the winter apartments (above: warmer and sunnier); but in this case, an apartment was prepared on the upper floor for the King, who liked to hunt on nearby land in the Saint Germain forest.

The official distribution is the only one that counts: the ceremonial sequence; there are no auxiliary dependencies in it. In the lower and upper floors of the house the kitchens and warehouses and other offices and the servants’ rooms would be accommodated, which were also accommodated in two external pavilions, destroyed in the 19th century, which flanked the entrance, with room for stables and garages.

Stairwell

The lobby is necessarily central; and the stairwell opens on the right side. Behind them, the apartments are lined up; the sequence is modified to arrange the gala bedrooms (chambre de parade) in the corners, providing them with light and views of two facades; the usual bedrooms are retracted and from them there is access to some beautiful and fresh elliptical halls, designed to look out from under cover in the small lateral exedras, over the moat.

The distribution of the upper floor, with gala bedrooms (chambre de parade) in the corners, is clearer: and it is what justifies the general form of the building, which he wanted to express. The main apartment is preceded by a large room; the offices or cabinets open onto terraces, and the large bedrooms look out onto balconies over the small porches of the garden façade.

There is a small central apartment on the third floor, which would enjoy nice views (which can be extended if you climb the lantern that crowns the entrance facade).

Lobby

The vestibule and staircase are resolved in exposed stone, excellently rigged, and the staircase is a small display of stonework. The lobby takes advantage of (and justifies) the two setbacks of the central street of the facades; and allows to make a stately set of classic orders in stone framed the two doors; and it is the most monumental room in the house. Since ancient times it has been highly admired (and rightly so).

Staircase of Honor

The solemn main staircase emulates the one Mansart designed years before for Blois. The d’honneur staircase climbs uncovered inside its box: above the main floor a first vault supports a beautiful cantilevered gallery; above it, the dome and its lanterns telescopically close, creating a stupendous spatial effect. The cantilevered gallery would allow discreetly accommodating some musicians when they wanted to give a particularly notorious reception.