American Railway Travel

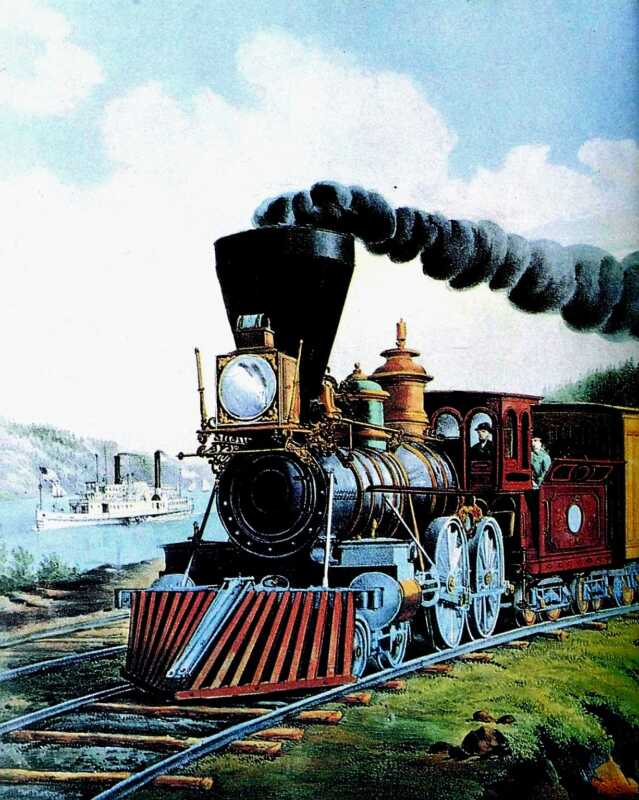

The first commercial use of railroads to transport paying passengers came in 1830, but it was just as well to take a horse-or a horse-drawn conveyance. Stagecoaches could take you nearly anywhere, so railroads remained largely a nov- elty until 1850, by which time there were 9021 miles of rails, mostly in the Northeast.

In the early days, the railroads usually followed the lines of least resistance in laying their tracks. The railroads went by rote to such an extent that, according to tradition, the standard gauge-which is the inside distance between the rails-was determined by the width between the wheels of the ancient Roman chariots. Early English stagecoaches, according to the legend, were built to fit the grooves Roman chariots had made. When the first English railroads were constructed, the tracks were laid to the gauge of the stagecoaches, and the railroad cars and steam engines were built to fit that gauge.

Then, when the engines made in England were brought to America, the tracks were laid to match their gauge; and that is why, the story goes, the standard gauge in the United States is the odd figure of four feet, eight and a half inches.

Railroad building in the southern states had made little head- way in the first half of the nineteenth century, and in the Midwest only three important lines were begun. In New England, where the country was the most densely populated, the progress was greater, so that by 1850 nearly all the important trunk lines in that region had been completed.

The ten years following 1850 were far more important in railroad history than the preceding decade. The increase between 1850 and 1860 was from 9021 to 30,635 miles, a result of several factors. The southern and midwestern states were developing, thereby creating a demand for greater transportation facilities. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 until 1857 brought the people of the United States highly prosperous times.

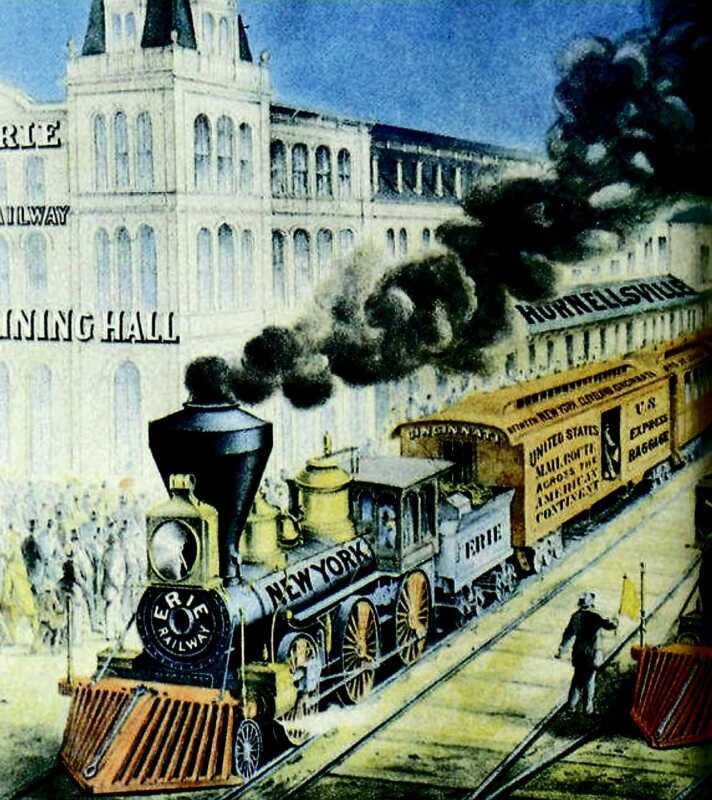

Business activity in all lines was keen, and railroad building shared with other enterprises in this prosperity. During the decade following 1850 many of the trunk lines of he large railroad systems of the present day were completed. The Erie Railroad joined New York with Lake Erie in 1851, and the Baltimore & Ohio reached the Ohio River the same year. The construction of long lines proceeded rapidly in the states east of the Mississippi River and north of the Ohio.

Atlantic seaboard to Chicago by rail

By 1853 it became possible to travel from the Atlantic seaboard to Chicago by rail. In the following year, the Chicago & Rock Island connected Chicago with the Mississippi River. Land grants, state sub- sidies, and prosperous times combined to foster the rapid spread of the railroad net in the Midwest. This lasted until 1857, when the good times were interrupted by a panic. Railroad building was then so seriously interrupted that it had not regained its previous activity when the Civil War stopped nearly all indus- trial progress for half a decade.

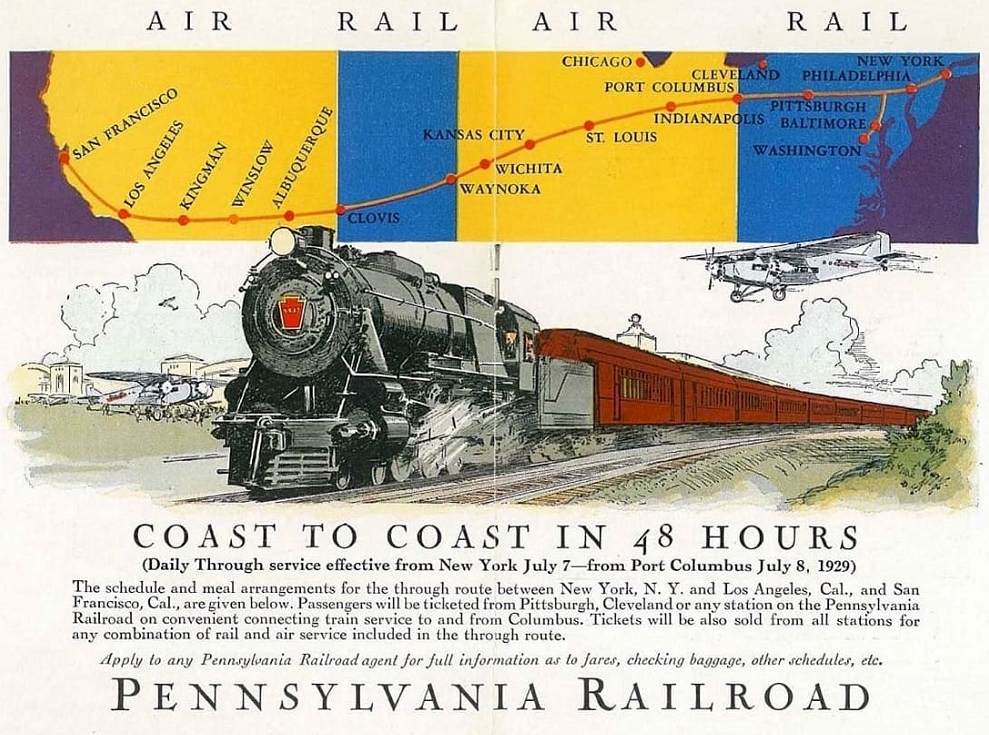

Indeed, it was not until the golden spike was driven on 1 May 1869 at Promontory, Utah, that the nation was truly united. With that momentous event, a rail line stretched uninterrupted from San Francisco to Omaha, and then from Omaha to Chicago, where it connected to the already existing American rail net- work in the Northeast, the South and the vast industrial heart- land around the Great Lakes.

The Sleeping Room in 1861

One of the best accounts of American rail travel in the years before the Pullman era was related by an anony- mous Englishman concerning his trip from Albany to Buffalo in 1861 on the New York Central.

The conductor, seeing him walk about the platform, eyeing the several carriages, asked with sagacious forethought,

- ‘Sleep- ing car, mister? Going through, stranger?’

- He replied, ‘Yes,’ and followed the quiet, sallow man into the last carriage, lettered in large red letters on a sunflower-yellow ground, Albany and Buffalo Sleeping Car.

‘I go in and find an ordinary railway carriage; the usual filter, and the usual stove are there; and the seats,” said the traveler. ‘Two and two, are arranged in the old quiet procession, turning their backs on each other glumly, after their kind. I ask how much extra I must pay for a bed.”

- ‘Single-high, twenty-five cents; yes, sir,’ said the conductor. ‘Double-low, half a dollar; yes, sir.”

The traveler ordered a ‘single-high’ (without at all knowing what was meant), and as he paid his twenty-five cents, the bell on the engine begins to get restless, the steam horses snorted and champed and struggled. Ten other persons entered, and ordered beds and pay for themselves, with more or less expectation, regret and wrangling.

More bell, more steam, smothering them all with white-a wrench, a drag, a jolt back half angry, as if the engine were sulky and restive, and they were off. The signal posts and the timber yards flew by, and they were in the open country, with its zigzag snake fences, Indian corn patches and piles of orange pumpkins. Ladies came in from other carriages. (Unlike British trains of the period, a restless or seeking traveler could walk through the American train.)

Seated in twos and twos, some musing, some chatting, some discussing the irrepressible squabble,’ many people were chewing or cutting plugs of tobacco from long wedges, pro- duced from their waistcoat pockets. The candy boys came

One hour from Albany they were at Hoffman’s; twenty min- utes more, at Amsterdam; fifty minutes more and they had reached Spraker’s-pure Dutch names all, as though old Henry Hudson had christened them himself. Between Little Falls and Herkimer, the officer of the sleeping car entered, and called out: Now then:

Misters, if you please, get up from your seats, and allow me to make up the beds.

Two by two they rose, and with neat trimness and quick hand the nimble Yankees turned over every other seat, so as to reverse the back, and make two seats, one facing the other. Nimbly they shut the windows and pulled up the shutters, leaving for ventilation the strip of perforated zinc at the top of each. Smartly they stripped up the cushions and unfastened from beneath each seat a canebottomed frame secreted there. In a moment, by opening certain ratchet holes in the wall of the carriage, they slid these in at a proper height above, and covered each with cushions and sleeping rug.

The Englishman went outside on the balcony, to be out of the way, and when he came back the whole place had been trans- formed. No longer an aisle of double seats, it was like a section of a proprietary chapel put snug for sleeping, with curtained berths and closed portholes.

‘Oh, dexterous genius of Zenas Wallace and Ezra Jones, conductors of the New York Central Railway!‘ he recalled. The lights of the candle lamps were dimmed or withdrawn, and a hushed stillness pervaded the chambers of sleep. No sound broke it but the clump of the falling boots, and the button slapping sound of coats flung upon benches. Further on, within a second enclosure, one could hear voices of women and children.

A fat German haberdasher, from Cincinnati, was unrobing as if he were performing a religious ceremony, and, indeed, as the English gent noted, ‘sleeping is a rehearsal of death, and seems rather a solemn thing, however we look at it.”

The bottom berths were singularly comfortable at first, with room to wander and explore, to roll and turn, and with curtains to hush all sound, and keep off all inquisitive rays from Zena’s or Ezra’s portable lamps. There was, indeed, twice the room that one would have had aboard an Atlantic steamer such as the one in which the Englishman would have come across.

In a steamer berth:

One could not sit up at night without bumping his or her head against the bed planks above, and could not turn without pulling one’s bed covers off. As for a heavy sea, there was no keeping in bed at all without being lashed in.

‘Now, I mount my berth; for sleep is sympathetic, and when everyone else goes to sleep I must, too,’ said the Englishman. There were two berths to choose from, both of them just wicker trays, ledged in, cushioned and rugged, one about half a foot higher than the other.

‘Several have turned in, and are snorting approval of them- selves and of sleep as an institution generally,’ he recalled of his fellow passengers. ‘Others, like young crows, balancing on the spring boughs, swing their Yankee legs, lean and yellow, from the wicker trays, and peel off their stockings or struggle to get off their boots.

Samsung Store: Galaxy Z Fold4

‘I clambered to my perch. The tray was narrow and high. It was like lying with one’s back on the narrow plank thrown across a torrent. If I turned my back to the carriage wall, the motion bumped me off my bed altogether, if I turned my face to the wall, I felt a horrible sensation of being likely to roll down backwards to be three minutes afterward picked up in detached portions. I lay on my back and so settled the question; but then the motion! The American railways are cheaply made and hast ily constructed. They have often, on even great roads, but one line of rails, and that one line of rails is anything but even.

Through the night he heard the clashing of the bell on the engine at Chittenango, Manlins, “Canton, Jordon, Canas- erago’ and all the other places with Indian, classical or scriptural names. When he peered through the zinc ventilator into outer darkness, a flying scud of sparks from the engine funnel did not serve to divest his mind of all chances of being burned. Then there were blazes of pine torches as they neared a station-a fresh bell clamor and jumbling sounds of baggage, slamming doors and itinerant conductors.

I lay on my back on that wicker shelf of the sleeping car,:

He continued, and in vain offered up prayers to the great black King Morpheus of the mandragora crown and ebon sceptre… No, zigzag goes the car, rush, jolts, and now I begin to believe the old story of the stoker and engineer playing cards all night, and now and then leaping the train over a “bad place.” crying. “Go ahead; let her rip!”

At last a precarious and fragile sleep crusts me over, but it is like workhouse food; it keeps life together, but not amply or luxuriously. So blessed daylight reluctantly and sullenly returns, and went to sleep. one by one we wake up, yawn and stretch ourselves. There is something suspicious in the haste with which we all flop out of bed; no really comfortable bed was ever left with such coarse ingratitude. Presently to us enter Zenas and Ezra, not to mention a new passenger from Crete, regardless of the somewhat effete atmosphere of our carriage, and proceed to adjust the seats.”

The beds would be rendered invisible in a few minutes. The wicker trays moved out and cushions stripped off, curtains put up to the roof supporters. Underpinning bolts-Click, jolt, and they were chair seats once more, and then through the open windows came a draught of pure air that freshens our frowzy and disheveled crew

In the wash room, the one dirty scrub brush fastened to the wall by a chain gave the whole place the appearance of ‘the cell of a dead barber.

The Englishman was swift to mention that the second time he took a railroad sleeping car, he really did sleep, and the third time, he slept well. “So much for habit,” he added.

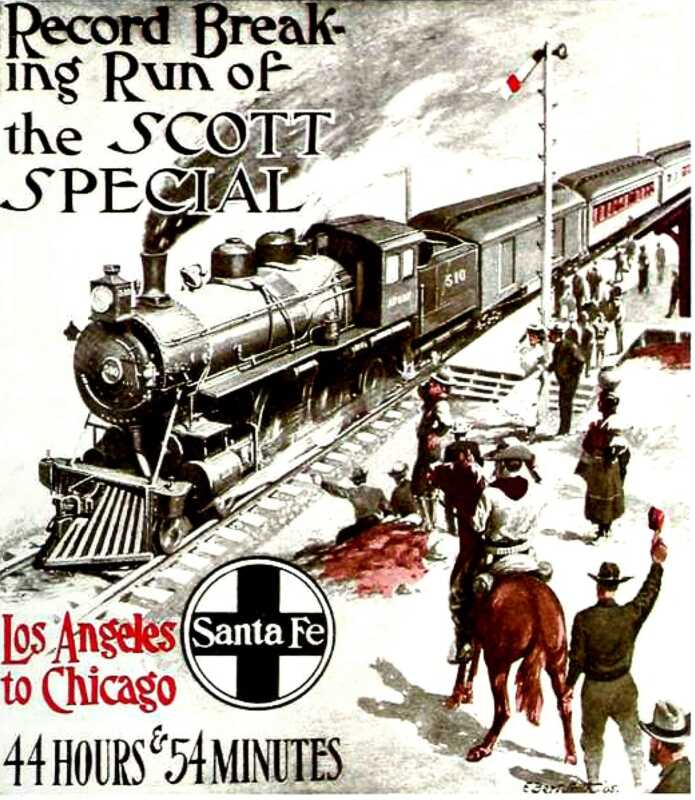

The Scott Special – Santa Fe Railway

E Bert Smith painted the cover for the original edition of Frank Newton Holman’s account of the run of Walter Scott’s Death Valley Coyote. He put Teddy Roosevelt on horseback viewing the train, but, in fact, the President was in the White House when Scott telegraphed him from Dodge City that ‘An American cowboy is coming East on a special train faster than any cowpuncher ever rode before: how much shall I break transcontinental record?’

After the run, ‘Death Valley Scotty’ retired to the Mojave to live in a castle he built there, which in turn became a famous resort known as, of course, ‘Scotty’s Castle. On nearby Interstate 15, motorists watch their speedometers hover at 65 and dream of Scotty’s 84 mph dash across the desert.

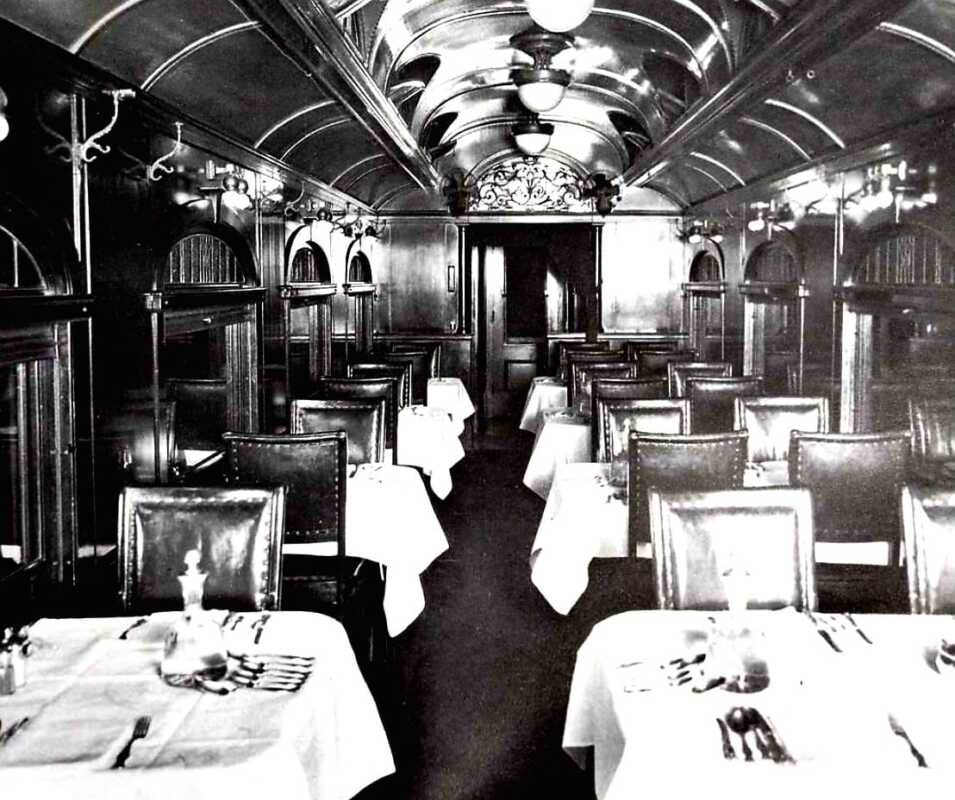

American Railway Travel – The Dinning Car

Just as railroads expanded in the mid-nineteenth century, so too did the amenities that they provided for their cus- tomers, and this had a great deal to do with ushering in the golden age of rail travel. In the early days passengers either brought their own food in boxes, or sometimes the train stopped so they could eat at station restaurants. The food was always terrible, usually black coffee made once a week, dry, salty ham, questionable eggs fried in rancid grease and put between slices of stale bread.

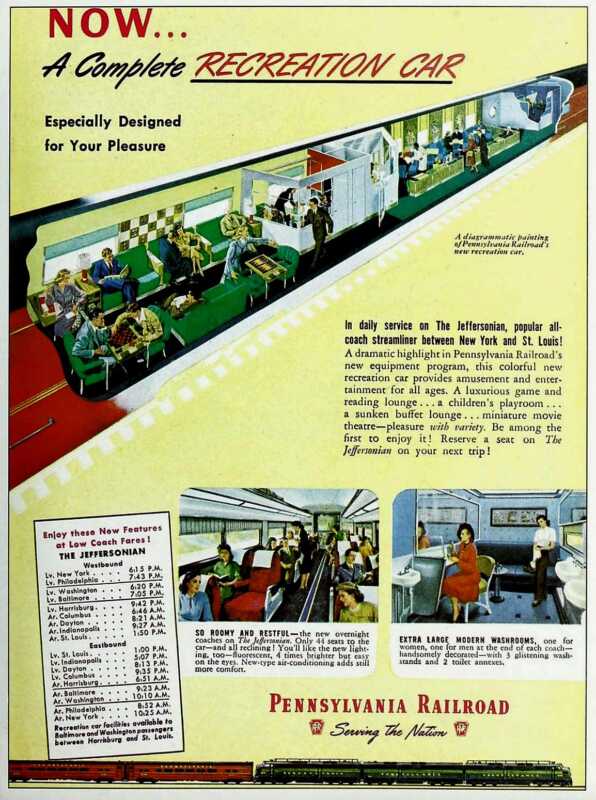

The first diner a baggage car containing a counter and high stools was put in service in 1862 on the old Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad (later part of the Pennsylvania system). Its menu was oyster stew, crullers and coffee. Five years later, George M Pullman installed his first eating car, the President, on the Great Western Railroad in Canada. It was a ‘hotel coach, which was a sleeping car equipped with a kitchen. A year later his first diner in the United States, the Delmonico, went into service between Chicago and St Louis on the Chicago & Alton line.

In the 1880s, railroads began using diners as a means of building good will. Some of the old wooden diners had ornate chandeliers, potted palms, rubber plants and other flora sitting in elaborate vases in niches along the walls. The menus and prices were utterly astonishing by current standards. A typical dinner menu on a Chicago to Omaha train included: sirloin, tenderloin, porterhouse or venison steaks, prairie chicken, snipe, quail, golden plover, blue winged teal, woodcock, broiled pigeon, mallard, widgeon, canvasback or domestic duck, wild turkey, veal, mutton, chicken, roast port, sixteen relishes, eleven clam and oyster dishes, five fish dishes, fifteen kinds of bread, many soups and desserts any or all for 75 cents.

As late as 1907, the New York Central’s dollar breakfast started with fresh fruit and baked apple, a choice of oatmeal or shredded wheat, Lake Superior whitefish, broiled or salted mackerel, choice of tenderloin or sirloin steak, ham or bacon, mutton chops or sausages. Another course was broiled chicken on toast with fried mushrooms, five styles of eggs, six of potatoes, an assortment of breads, wheat or buckwheat cakes, preserved fruit, marmalade, coffee, cocoa, milk or English breakfast tea.

A Short Glossary of Dining Car Staff Terminology

- Captain: The conductor.

- China Cabinet: The cone shaped strainer used for deep fat Nellie frying.

- Crew’s Portion: A double order of food, whether actually for a crew member or for a patron.

- Del Robie: The large oval tables on both sides of the center of the dining car.

- Dog House: The main refrigerator.

- Doggie: An adjective describing a waiter who is not feeling well.

- Dresser: The counter where vegetables are prepared.

- Eyes: Block signals. Flat: A dining car when full.

- Forty-eight and standing: A full dining car. (They typically had 48 seats) with people waiting to be seated.

- Getting in some time: Being lazy.

- Going upstairs: Serving a meal outside the dining car.

- Nellie: A room service customer, or someone who is taking his or her meal outside the dining car.

- Pearl Diver: One who washes dishes. A synonym for Turtle. Putting him on the boss’s desk: The process of turning in a waiter for an infraction.

- Smoke Wagon: A steam locomotive,

- Struggle Buggy: An old dining car. Switch: An order to stop talking.

- Television: A dishwasher with a plate glass window.

- The Hole: The wide shelf by which the kitchen is separatedfrom the pantry.

- Tubbing: the process of a waiter refusing to pool his tips. Turtle: One who washes dishes. A synonym for Pearl Diver. Up a tree: Condition of not knowing what one is doing.

On overnight trains

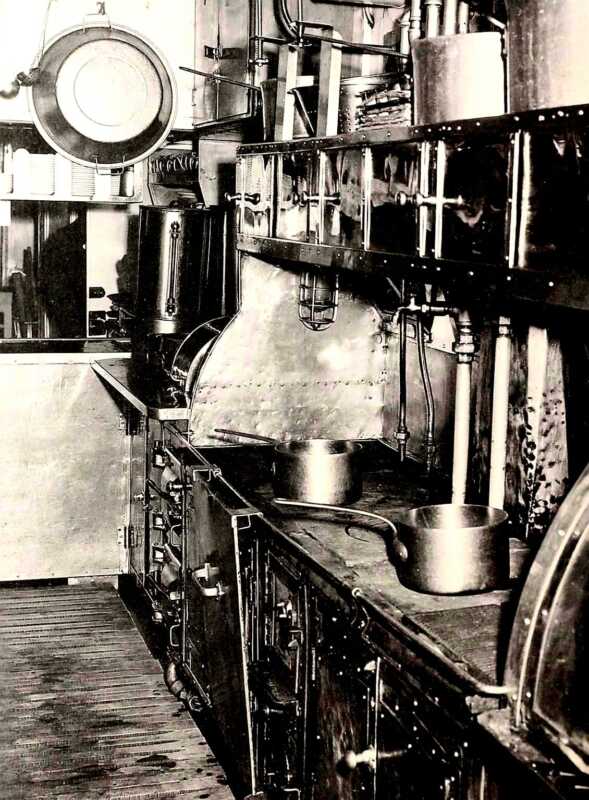

the dining car day began as the third cook started the kitchen fire at 4:30 am. The rest of the crew would awake 30 minutes later.

Dining car crews usually reported for duty four or five hours before the big overnight trains pulled out to prepare roasts, most of the bread and vegetables and all the desserts. The cooking that was done after the train journey began was usually confined to steaks, chops, short orders or perhaps some special dish, such as game, that passengers may have brought aboard.

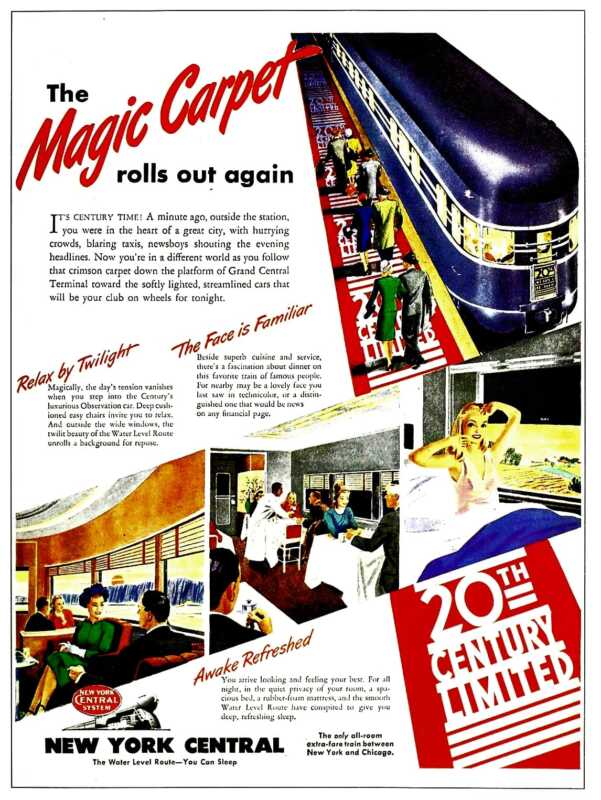

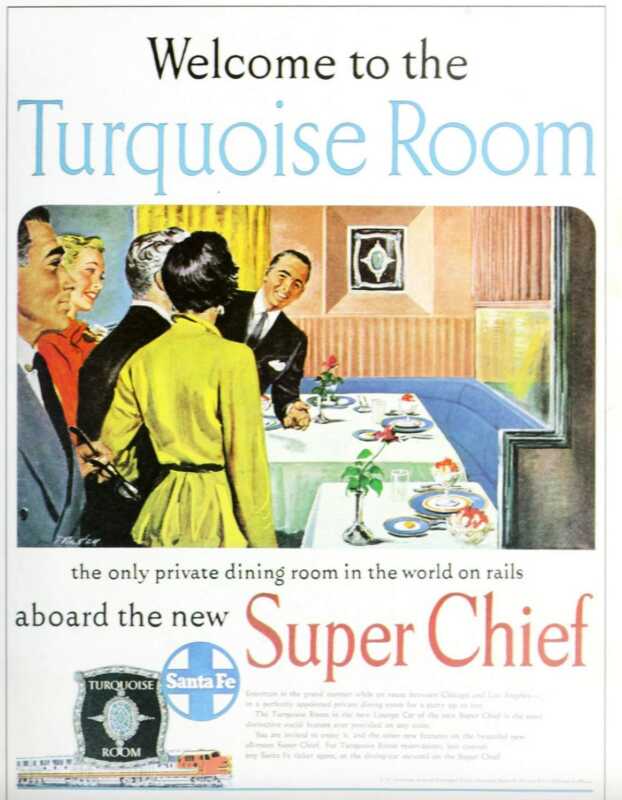

In the age of efficiency that marked the end of the golden age in the 1950s, the number of waiters on a train ranged from one on a club car to 10 on some big twin units. The latter consisted of an 84-foot diner, adjoined by a similar length car containing the pantry, kitchen and a lounge on daylight trains, like the Pennsylvania’s Congressional Limited. On overnight trains like the Twentieth Century Limited, the crew quarters were alongside the kitchens and passenger lounges were located elsewhere.

A twin unit cost about $400,000. It carried $6500 worth of portable equipment-2500 pieces of linen and 2500 other pieces of silver, china and glass. On an overnight trip it would carry about $650 worth of food and $150 worth of liquor.

The chef also handled roasts, soups, sauces and the inventory of supplies. Running along the car’s outside wall was the dish- washer, waist-high cabinets and an ice chest for fish. The cooking ranges were placed along the wall that separated the kitchen

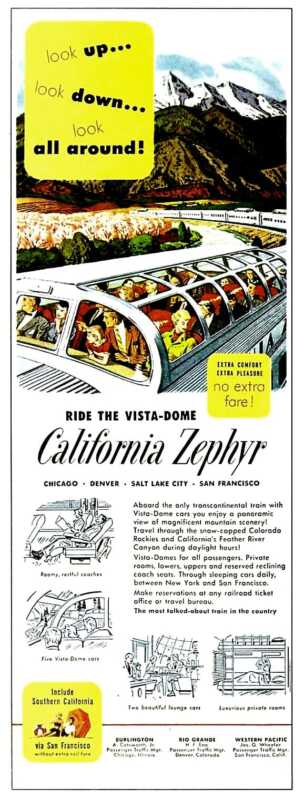

Right: Santa Fe passengers of the 1950s eagerly await their dinner. Below: A Santa Fe club car sporting a southwestern motif.

from the corridor. Most ranges were heated by logs of com- pressed sawdust, although the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Illi- nois Central and the New Haven introduced electric ranges in the 1950s. The main refrigerator (the ‘Dog House’), which was also electrified after 1945, was across the kitchen’s rear side. This was the station of the second cook, who had charge of the refrigerator, salads, vegetables and baking.

The third cook, who worked next to the chef,i handled steaks, chops and all food cooked on the charcoal broilers. Next came the assistant second cook. He handled egg dishes, hot cakes and potatoes. The fourth cook, who worked alongside the second cook, was in charge of the steam table and the dishwasher.

To save money

Railroads started making the fourth cook a swing man. He might help serve lunch and dinner between New York and Pittsburgh, then leave the train at Pittsburgh and help serve breakfast and lunch the next day on a New York bound train.

Dining car supervisors constantly patrolled the railroads, getting off a train heading in one direction, then boarding another one going the opposite way. They tasted the food, observed the crews’ deportment and inspected standards of cleanliness. When an inspector was on the prowl, crews passed the word in several unique ways from one train to another. If an inspector got off an eastbound train at Cleveland, for example, its crew would signal all westbound trains they met.

The warn- ing might be a ketchup bottle sitting in a certain window, a waiter waving a tablecloth, a cook holding a frying pan at arm’s length or a towel tied on the safety bar of the kitchen door that opened from the side of the car. When the late Major John F Trout was superintendent of the Pennsylvania’s dining car service, the signal between trains that he was out on an inspection trip was a cook standing in the open door holding a large fish by the tail.

The Twentieth Century Limited, which considered itself a sort of club, was inhabited by ‘regulars’ (commuters) between Chicago and New York. Many of these expected to be recognized and catered to. The dining car staff always cited Spencer Tracy as having perhaps the strangest food habit of the many movie folk who regularly rode the Century. He always had a waiter awaken him at 5 am, whereupon he drank a full pot of black coffee and went back to bed. Bing Crosby often whistled and sang while going to the diner, and Morton Downey would sing all night if he could round up a barbershop quartet.

The Pullman That Got Away – American Railway Travel

Tom Burnley is a man most of us have never heard about. Yet his name is mentioned in the same breath with those individuals who refused to back Henry Ford in his early days-with those foolish few who could have bought, at the birth of Coca-Cola, a half-interest in the company for a pittance but thought it too long a shot to risk.

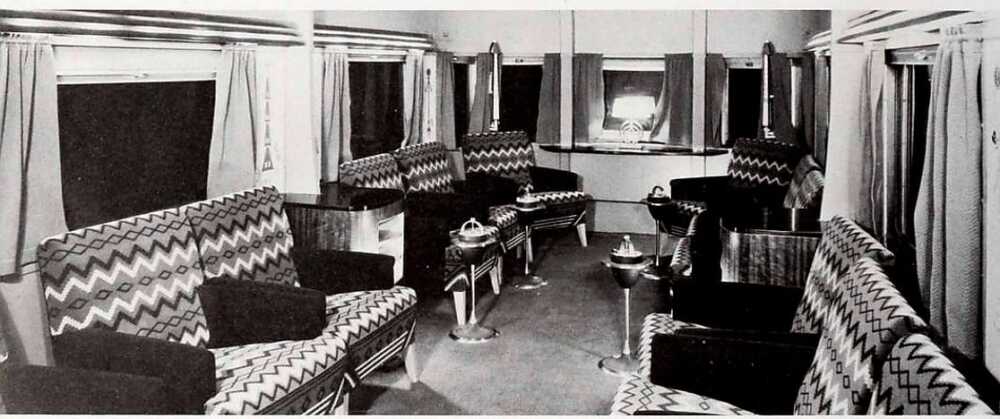

Pullman “Marco Polo” Sleeper/Lounge/Observation Private Car

It happened back in 1860 in Canada. The Prince of Wales (who later was to become King Edward VII of England) was scheduled to make a tour of the Canadian provinces. Looking over the Prince’s itinerary, the Governor General of Canada immediately saw that there would be much overnight travel between cities, a situation that would involve finding some sort of sleeping arrangements for the crown prince. He advertised for bids for the construction of a railroad coach which would be used, besides ordinary travel, for sleeping quarters for the dis- tinguished visitor while enroute.

Among the designs submitted for the unheard-of contraption were those of Tom Burnley. His plans were chosen and he got the government go ahead. His coach, an elaborate creation, was built in the Brantford, Ontario railyards under the supervision of Burnley himself. This coach boasted hand-carved, gilded coats of arms on each side, marble wash basins and counters, finely paneled walls, overstuffed beds, couches and chairs, and heavy, tassel ringed draperies.

History of Luggage

Prince finally arrived

When the Prince finally arrived and saw his new home on wheels, he was delighted with it. He used it in preference to hotels, and it was his official address for the two months of his tour.

Poor Tom Burnley could not see the future of such a mon- strosity and blindly forgot to patent his coach. It was beyond the realm of his imagination that such a sleeping coach could be put into widespread use. After all, he thought, who would want to sleep on a train?

But at that same time, there was also another unknown, who was coming to Brantford on occasional trips. His name was George Pullman and he was employed by the Buffalo & Lake Erie Railway. Having occasion to visit the yards at Brantford, he heard about the strange railway coach that was being built, and out of curiosity went to have a look.

Being no idle dreamer, he realized the possibilities of the sleeping coach, and after making careful sketches and asking many pointed questions, he returned to Buffalo and secretly began to construct a coach of his own. Duly constructed and patented, the coach was put into use on the railway. It was an immediate success, and by using shrewd business acumen in renting the cars rather than selling them, Pullman was on his way to becoming a millionaire.

So Tom Burnley’s invention, evolving from a gaudy Victorian sleeping coach designed for a king, became a blessing to weary travelers. But Tom Burnley himself has long been forgotten- hidden in the musty archives of inventors and inventions- remembered by a scanty few as an inventor who might had made a million if…

Related Post

- Wilmington & Western Railroad

- Oregon Scenic Railroad

- Jacobite Train

- Amazing Torist Trains

- Wilmington & Western Railroad

- Carson Train Route

Sources

All Aboard – Book on Amazon.com

The Beginnings of American Railroads – Library of Congress